How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love Hungarian Art

Like most Americans, even my fellow specialists in contemporary art, I have lived a long time with only the most rudimentary notion of what happened to art behind the Iron Curtain during the Cold War era. An ambitious and expansive new exhibition that fills two floors at Elizabeth Dee gallery in New York, With the Eyes of Others: Hungarian Artists of the Sixties and Seventies, changes that situation substantially. The show is the first in the United States to survey Hungarian art of those decades and introduces most of its artists in this country for the first time. The few who have previously debuted here—including Miklós Erdély, Tibor Hajas, Dóra Maurer, Gyula Pauer, Tamás Szentjóby, and Endre Tót—have been seen in the context of either global Conceptualism or Eastern European art as a rather monolithic whole, and not necessarily in the company of their compatriots. So the exhibition also marks a milestone in American understanding of a specifically Hungarian character in their work, and that of others.

With the Eyes of Others – exhibition view at Elisabeth Dee Gallery © Courtesy of Elizabeth Dee New York

Bringing together abstract painting and sculpture, Conceptual Art, documentation of performances and ephemeral happenings, video, sound art, mail art, graphic design, and concrete poetry by several overlapping coteries of artists, the exhibition posits a “neo-avant-garde,” an unofficial, even oppositional, art movement that existed in Hungary’s relatively more permissive society by remaining just cryptic and ironic enough to appear unthreatening to the regime. The curator, András Szántó—a distinguished historian, critic, and consultant in arts and culture who had remarkably never organized an exhibition before—occupies a somewhat privileged position in relation to this movement, having grown up partly in its milieu and, as a young man, having worked as a translator for László Beke, its chief apologist. Full disclosure: I also have a special relationship to With the Eyes of Others, having been called in late in the day to supervise the show’s installation. That experience allowed me to spend more time, up close and personal, with the works of art than, I assume, any other critic in New York, and that face time with these historical objects has undoubtedly colored my thoughts about them.

Szántó sagely opens the exhibition with some of the works most readily accessible to an American audience, the abstract paintings and sculpture, which appeal even to casual viewers with little knowledge of the cultural and political conditions that produced them. The first work, facing the entrance, though, seems quite specific to its Hungarian origin. Imre Bak’s 1976 NAP-BIKA-ARC (SUN-OX-FACE), a three-meter-wide painting on two canvases, splits the difference between hard-edge abstraction and folkloric pictograph. Its nearly Op Art-intensity of color and strict geometry of circles, half circles, stripes, and a triangle beguile the spectator, who toggles between representational readings of the motif as abstract sunset or horned bovine head. Bak’s work combines Pop legibility, retinal dazzle, and a formal purity that harks back to a lineage of early modernist abstraction, yet, despite its sophistication, it also possesses a childlike innocence. It’s not easy to think of a Western equivalent from this era that evinces a similar set of characteristics, and, with its storybook charm, the painting makes both a spectacular and a slightly misleading introduction to the exhibition.

With the Eyes of Others – exhibition view at Elisabeth Dee Gallery © Courtesy of Elizabeth Dee New York

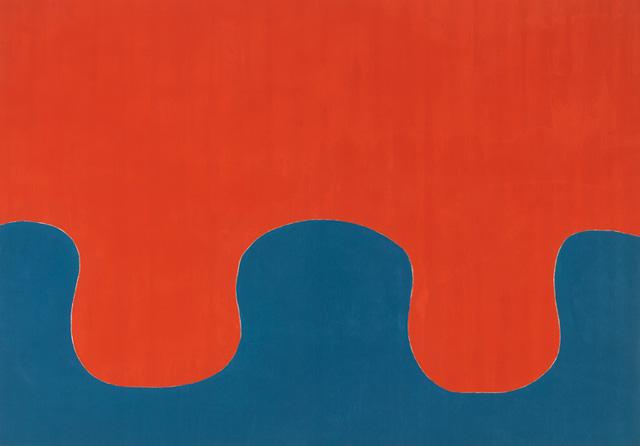

Other paintings in this first section of the exhibition appear to follow far more familiar avenues of artistic approach, although the inevitable and automatic comparisons that we make of the Hungarian works to their American and Western European counterparts may foreclose some of their particular meanings. A 1967 work by Bak, Purple-Green-Blue, with a meander of vivid rose edged in olive on a blue ground (or possibly something like the reverse; as with much advanced painting of the time, it oscillates our perception of figure and ground ), seems like the love child of 1960s American painters Paul Feeley and Nicholas Krushenik. Paintings by István Nádler have similarly funky feel, incorporating elements of Pop, Op, Post-Painterly Abstraction, and Minimalism. The multicolored curves and templates of an untitled 1968 canvas appear to channel both Frank Stella’s Protractor series and the coeval peacock logo of the television network NBC.

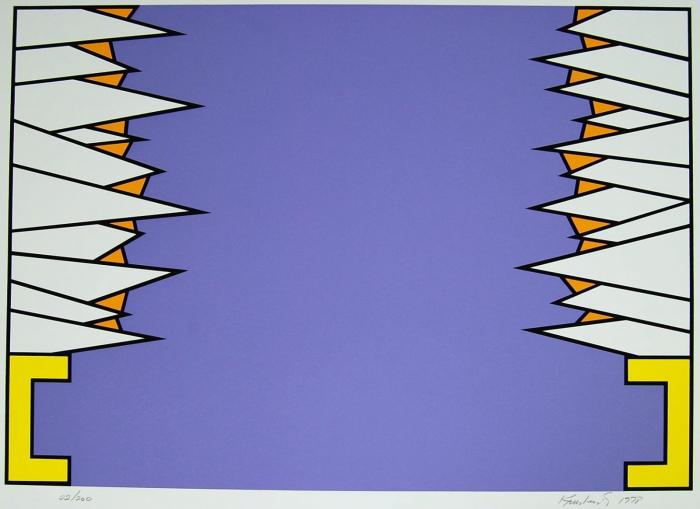

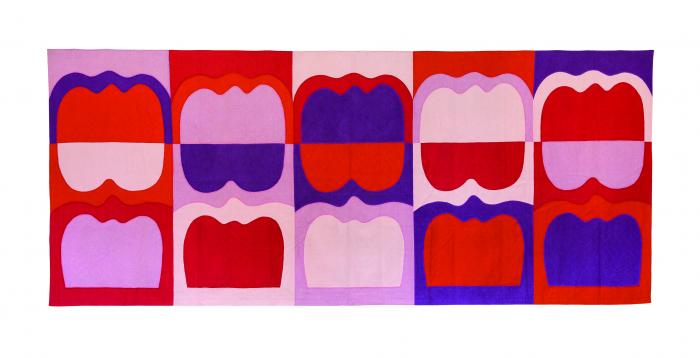

Nicholas Krushenik: Over the Rainbow, 1978 (Print, Serigraph on Somerset paper) Source: brightcolors.com

Paul Feeley: Untitled (January 12), 1962 (oil-based) Source: hyperallergic.com

Women, though underrepresented in the art world everywhere at this time, make a strong showing in Szántó’s exhibition despite their small numbers. Ilona Keserü Ilona’s Wall Hanging with Tombstone Forms (Tapestry) of 1969, a fabric applique nearly four meters long, with repeating curvilinear forms contained by an implied grid, impressively weds interests in abstraction and Hungarian folk art with textile art, then seen as indicative of “women’s work” and of feminist revisionism. 5 out of 4 I-III, a 1979 multipart painting by Dóra Maurer, represents, perhaps, the most rigorously Minimalist work in the gallery, its clean lines, and its focus on the grid and the square, articulated with diminishing means over a sequence of fifteen increasingly smaller panels, impart a sense of serious investigation not far from that of artists such as Donald Judd or Sol Lewitt, and their similar use of seriality, repetition with variation, and a systemic exhaustion within a delimited set of parameters. Maurer’s work, in fact, seems an embodiment or a relic of the artist’s thought, and watching the clarity of her thinking becomes rather thrilling, even as it reminds us of the now almost inconceivably blindered concerns that once held sway in art.

Ilona Keserü Ilona: Wall Hanging with Tombstone Forms (Tapestry), 1969 © Courtesy of the artist, Elizabeth Dee New York

With the Eyes of Others – exhibition view at Elisabeth Dee Gallery © Courtesy of Elizabeth Dee New York

One of the curator’s points about all this work, reiterated by others in the handsome catalogue that accompanies the exhibition, is that the artists created it in tacit defiance of the Socialist Realism officially sanctioned by the state, and that its obvious orientation towards the abstraction then dominating art magazines and galleries in the U.S. and Western Europe added to its understatedly subversive charge. Szántó also notes that the Hungarian artists worked in the absence of a market and possibly without the hope of one. As convincing as this sounds, one does wonder about the aspirations with which these paintings were meticulously made and then stored and preserved for some forty years or more. Their pristine condition now speaks to some sort of eye towards posterity.

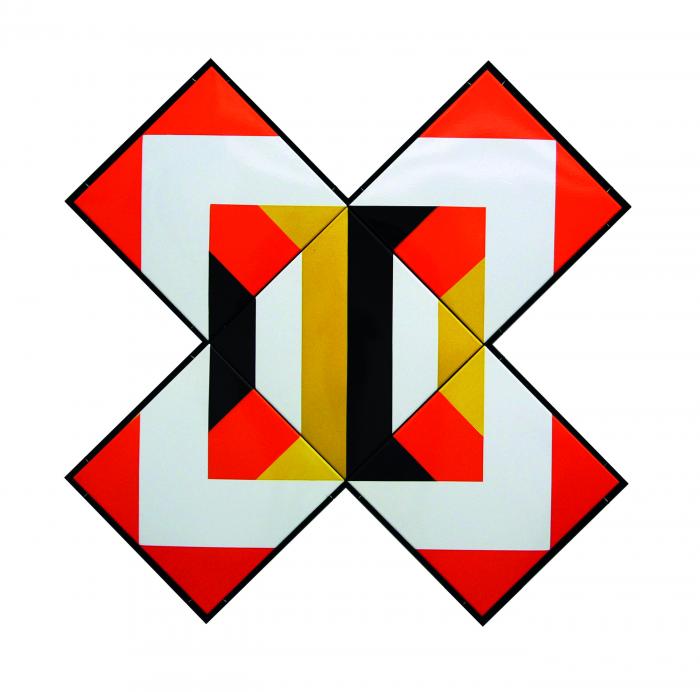

Artists associated with the Pécs Workshop manufactured four other works in this section in the Bohnyád enamel factory in the town. Károly Halász’s Radial Enamel I-IV, 1969, looks to Op Art for its dynamic composition, perhaps to Victor Vasarely, who himself was from Pécs, while Relation, 1971, by Károly Kismányoky seems to hark back to Constructivism. Imagination, 1972, and an untitled work from the same year by Sándor Pinczehelyi look as much like corporate branding of the era as they do like “high” art. These enamel paintings obviously pay homage to the Telephone Pictures of Moholy-Nagy, another great Hungarian forebear, but their symmetrical designs baked onto metal plates remind me of mid-century patio furniture and coffee tables. This whiff of the thrift store raises a problem that affects some of the other abstract works in the exhibition, namely that their easily legible reliance on Western models can make them appear as also-rans in the international arena.

Pinczehelyi Sándor: Imagination, 1972 © Courtesy of the artist, Elizabeth Dee New York

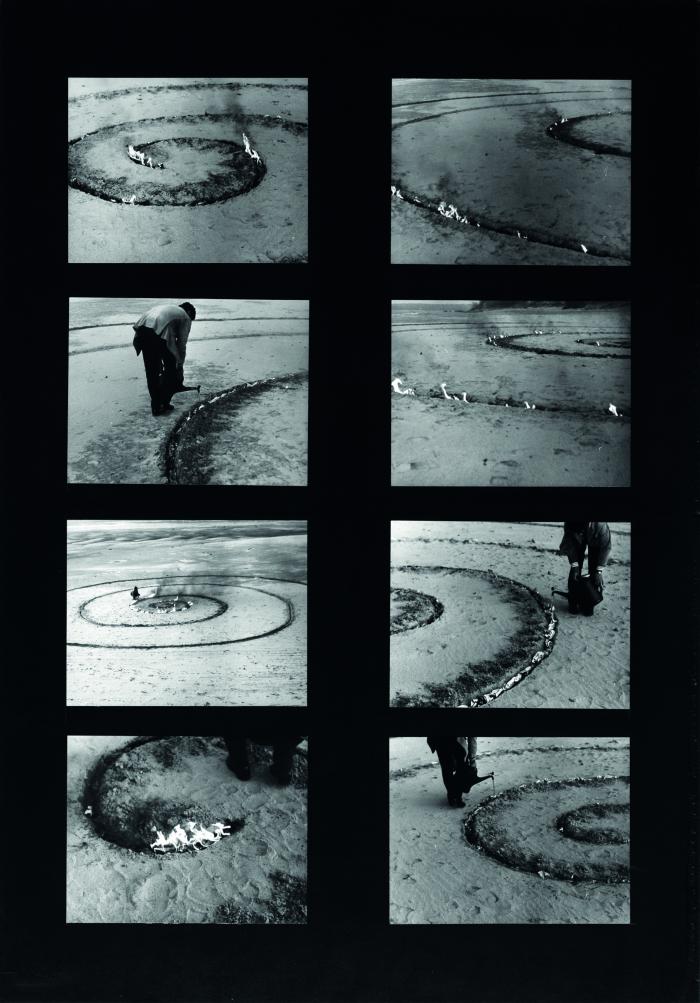

Interspersed with the abstractions on the first floor of the gallery are a number of Conceptual and performance works that also demonstrate the Hungarians’ hunger for the West in their direct citation of other artists’ works. Halász, who seems to have been protean in the variety of his output during these years, upon hearing of the death of Robert Smithson in 1973, dug a large spiral in the mud on the banks of the Danube, set it on fire, and photographed the event. For Robert Smithson’s thirty-two black-and-white prints mounted on four black panels make for a poignant tribute, both to the American earthworks artist and to Halász’s ostensible yearning for connection with an art world outside his country’s borders. Even more touching are the nine documentary photos of a 1974 action Halász organized. In the absence of a written description of the day’s activities, what exactly occurred at the event, titled simply Performance, remains unclear, but the photographs show a group of people gathered in a natural setting and watching some sort of happening. The real punctum in the images, however, is the stack of cardboard boxes that seems to serve as a signpost, clumsily affixed with labels of famous art galleries in the U.S. and Germany—Leo Castelli, Margo Leavin, Galerie Müller—as if those foreign institutions had sent something to Hungary, a kind of embodiment of an affectingly unfulfilled (until now) desire to have the outside world aware of the existence of the Hungarian artists, as they themselves kept abreast of developments elsewhere.

Károly Halász: Hommage for Robert Smithson, 1973 © Courtesy of Elizabeth Dee New York

Upstairs, the exhibition assumes a different character. The second floor lacks the color and scale of the paintings downstairs, and holds mostly black-and-white photographs, works on paper, a few small sculptures, and a couple of videos playing on monitors. Much of the performance documentation here has even less to contextualize it, either information internal to the photos or given to the viewer in the exhibition texts. We are left with striking images but little idea of the meaning, or even the subject, of performative works by Erdély, Hajas, Kálmán Szijártó, and János Vető. Szentjóby fares a bit better, and the three images that index his 1972 action Sit Out/Be Forbidden impart a sense of the risk that merely sitting in a chair on the curb of a Budapest street had at a time when the paranoia of the authorities would (and did) decree jail time for such an innocuous act.

With the Eyes of Others – exhibition view at Elisabeth Dee Gallery © Courtesy of Elizabeth Dee New York

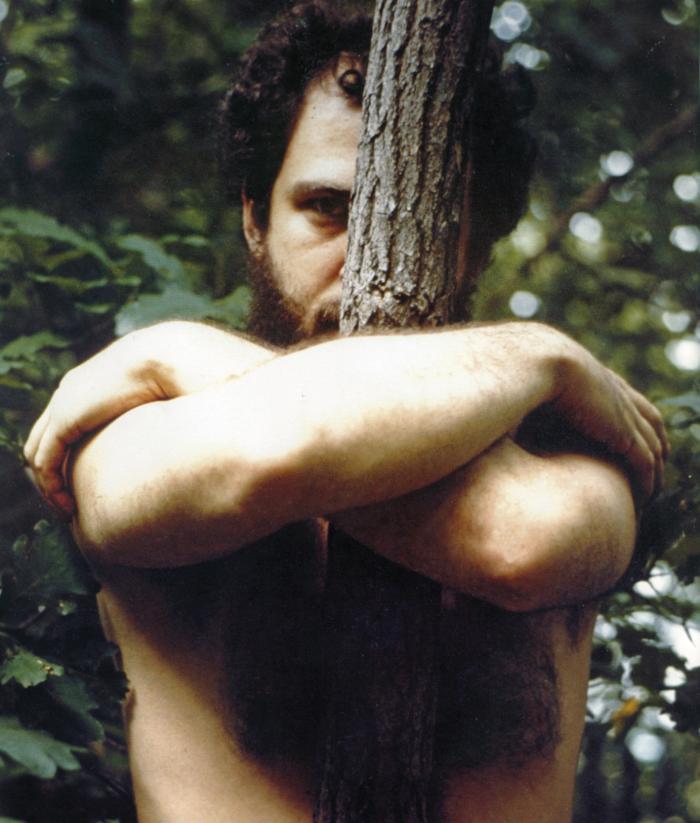

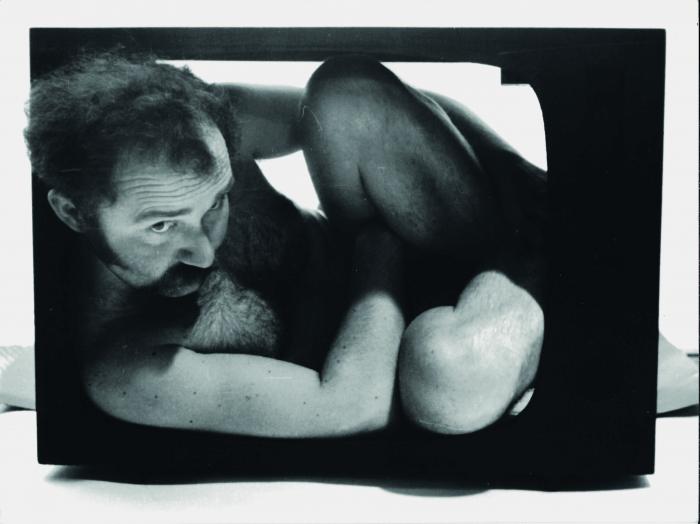

Boundaries between artistic genres were porous. While some of the work we might consider primarily Conceptual in nature appears rather facile (the works of Géza Perneczky—whose 1971 Concept Like Commentary features the word “art” written on ping pong balls, mushrooms, and a dandelion—feel particularly egregious in this regard), a number of artists combined photography, performative actions, and a sense of sly intellectual gamesmanship in statements that remain engaging and effective. Maurer’s 1976 video Proportions finds the artist using her body in various way to measure a long scroll of paper. The deadpan result proves, intentionally or not, droll. In his series Private Broadcast, from 1974–75, Halász photographed himself naked and curled into a cardboard box cut out to resemble a TV set. To be sure, this gesture encapsulates a commentary on state control of the airwaves, cultural repression of sexuality, perhaps of a homosocial character, and the limitations of private expression in public spaces, but it also reminds me of similarly teddy-bear-ish hippies of the era who employed their own hirsute bodies towards various ends. The 1969 series Myself Becoming One with the Tree by the American land artist Alan Sonfist, which pioneers a kind of ecological Conceptualism by depicting him naked and hugging variously sized trees, comes to mind.

Alan Sonfist: Myself becoming One with the Tree, 1969 Source: Museum of Fine Arts Budapest

Károly Halász: Private Broadcast I-IV. (detail), 1974-75 © Courtesy of Elizabeth Dee New York

In Poemim (1978/2016), Katalin Ladik portrayed herself in a manner similar to Halász as she held up an empty picture frame to her face, contorting her features in various comic expressions. Here, the target seems to be representation itself, which distorts individuals, particularly women, but the relation to television and early video art follows closely behind. In fact, her 1980 video Poemim, playing nearby, brings her grimacing to electrifying and sometimes disturbing life, accompanied by guttural, cartoonish vocalizations that reside somewhere between the avant-garde-ism of Yoko Ono and glossolalia. Along with Halász, Ladik stands out in the exhibition as a restless polymath, evinced by performative photo series, video, sound recordings, and notational drawings and prints.

Katalin Ladik: Poemim (detail), 1980 Passage from the film about Katalin Ladik entitled Ars poetica of the scream (directed by Kornél Szilágyi, Mediawave 2000 Ltd., 2010)

Yet what is most memorable in With the Eyes of Others for an American observer is the art that could not have been produced in the West, the works that make specific reference to the situation of Hungary and the Soviet Bloc. Symbols and indicators of Communism and the political situation of Eastern Europe appear in varied forms, from the obdurate brick with applied sulfur in Czechoslovak Radio, 1968 (1969/2015) by Szentjóby, implying only noncommunicative blunt force in the wake of Hungary’s participation in the Warsaw Pact invasion of Czechoslovakia, to the ironic humor of Tót’s Very Special Gladnesses Series - I am glad if I can stand next to you (1971–76), a photograph that shows the artist loitering at a monument to Lenin.

Tamás Szentjóby: Czechoslovak Radio, 1968 (1969/2015) © Courtesy of Elizabeth Dee New York

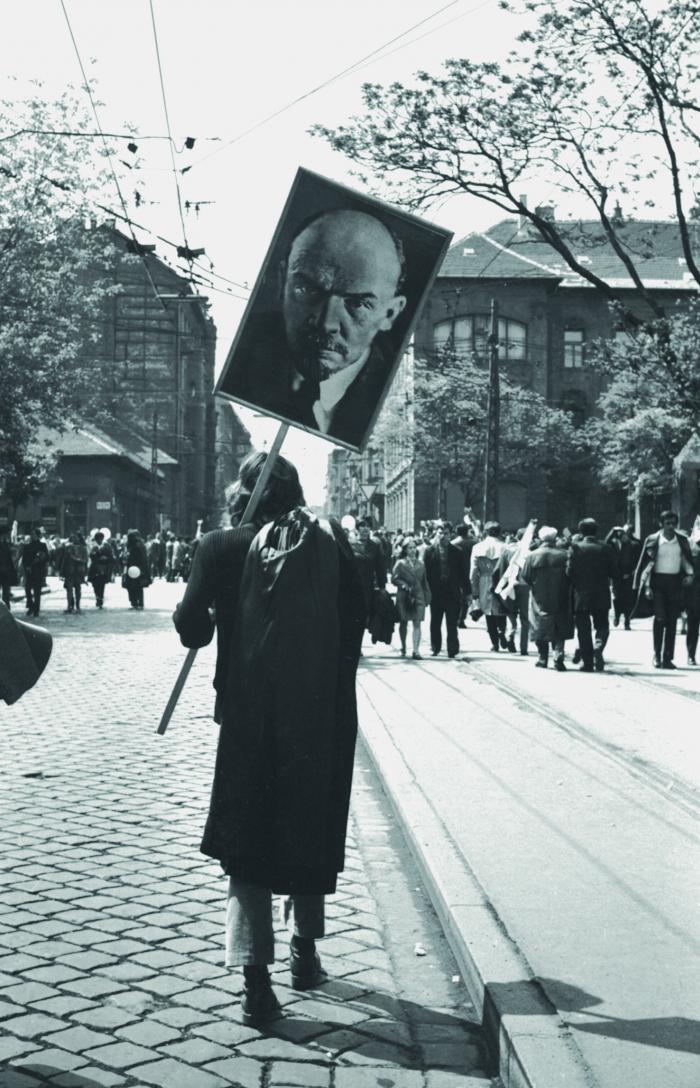

The thirteen photos of Bálint Szombathy’s Lenin in Budapest (1972/2016) picture the artist as a young hippie, with shaggy long hair and too-short trousers, walking around the city after the annual May Day parade with a protest sign that bears only a photograph of Lenin. Szombathy’s gesture was mute and presumably baffling. We can only wonder what passersby, much less the authorities, made of it. Would they have seen it as pro or anti-Communism? For or against the state? What meaning did the revolutionary leader have in Hungary in the 1970s? Or might people have perceived it as a deliberately confounding action, just incongruous and disconcerting enough to create a slight friction but not legible enough to force them to interfere? The latter seems the most likely and, to our minds all these decades later, the most appealing scenario. In our own times of disturbingly authoritarian-leaning governments both here and abroad, the exhibition suggests Szombathy’s strategy might be one to keep in mind.

Bálint Szombathy: Lenin in Budapest, 1972/2016 © Courtesy of the artist, Elizabeth Dee New York