Mysteries that everyone senses

An interview with Katalin Ladik

Katalin Ladik is an internationally recognized figure of the Yugoslavian and Hungarian neo-avantgarde, and she is among the great rediscoveries of recent years. The prevailing assessment of Ladik in Hungary has shifted dramatically. Originally stigmatized as the “naked poetess,” she is now regarded as a renowned and even defining figure on the Hungarian art scene as a visual artist, poet, and radical female performer. This shift clearly illustrates a more general turn in perceptions. Several important initiatives from recent years that were intended to spread this turn in broader circles are worth mentioning, for instance the Secondary Archive, which is the most recent history of art written by women. The Archive offers a detailed overview from distinctive perspectives of the oeuvres of women artists from Central and Eastern Europe.

Tünde Topor: I would be interested to learn more about the influences that affected you when you were young. Where do the roots of your art lie?

Katalin Ladik: My childhood experiences were decisive in my case, as they so often are for artists. I was born in 1942, so I was a child in the 1940s. I don’t remember the war, at least not specifically the war itself, but I do remember having nightmares. I realized this when my sister and I went to the movies and watched a war film. I cried, I was very, very frightened. It wasn’t the film that gave me the nightmares. I recognized something in the film that was already inside me. That’s where my fear of and admiration for machines came from. We lived in a dilapidated thatched-roofed loam house on the outskirts of Novi Sad. There was a hole in the wall of our room that we could crawl through to get outside. There was a barracks nearby, so the area was bombed. The military vehicles drove by our rented place, and in my eyes (I was looking at them from below), they were real machine monsters. At the same time, there were rusty farm machines at the far end of the yard. One of them might have been a harrow. I didn’t really know much about them at the time, and even today I don’t know which is which. But it was a great source of fun for me, because I could use it to make all kinds of sounds. I would bang and drum on the things around me, and of course I accompanied my music with song. I was in total ecstasy. High up in my seat, as if perched on a throne, I pretended that I was a queen playing a miraculous otherworldly instrument. I had never actually seen a musical instrument. I must have been seven or eight years old when, peering through the fence of the nearby Hungarian Cultural Center, I saw for the first time in my life a stage, a spotlight, and a troupe of people dancing and singing in flashy costumes. I don’t remember whether they were doing Hungarian folk dances or operetta. They may well have been doing a performance of Mágnás Miská. What struck me was the stark contrast: the difference between the world outside and the world inside, amplified by the slit in the fence as a frame. In my series Poemim, I distort my face by pressing it against a sheet of glass. The frame is there, as are my hands, because the movement of my hands is important, since I decide, like a cameraman, where the frame will be. The work of art is what lies within the frame. As an actress, I also thought that the art is what we present to the audience on stage. At the same time, I was excited by life behind the curtains, the other frame. I present the work of art, but I hide from the viewer the other, sweatier, more awkward part of it. Same thing in literature: we publish the poem, but we hide the background, the private life. The poet is sitting high on Olympus, but he has no body, only a manuscript.

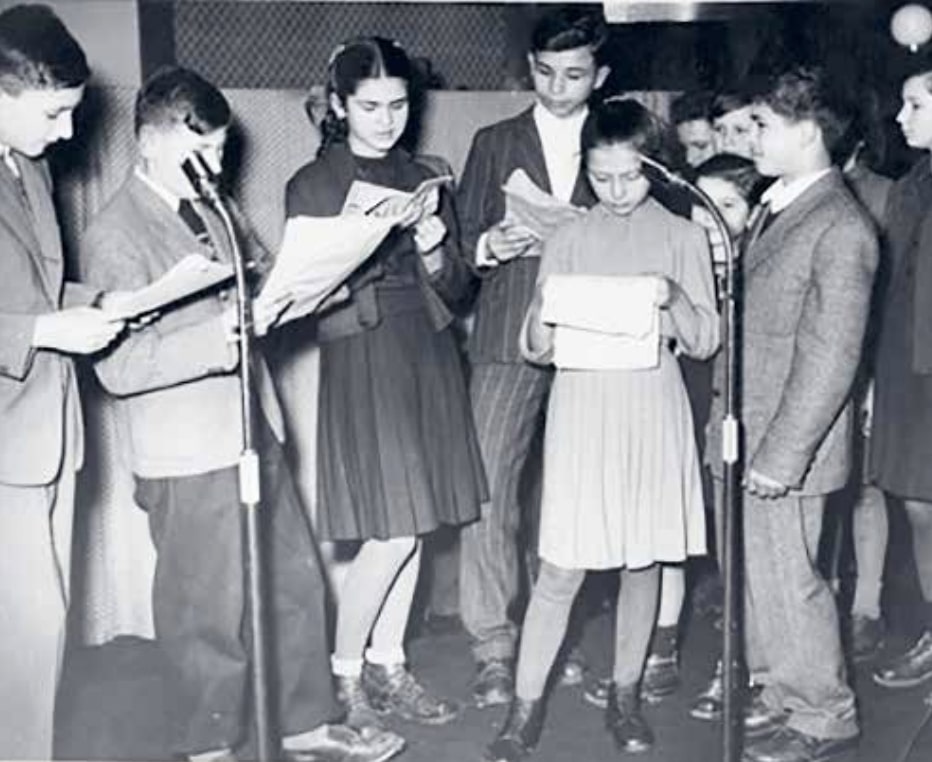

Let’s take a big jump in time. In 1962, when I was twenty years old, I committed myself to poetry and acting. I had made my first appearance on the radio as a child actor at eleven years of age, and I had soon made friends, as it were, with the microphone. A Hungarian theater was only founded in Novi Sad a decade and a half later, in 1977. When it came to radio, I already knew that what we say into the microphone is a form of theater too, but our audience, the listeners, they don’t see anything of what happens “under cover,” or in other words, during the rehearsals. We keep all the suffering, the challenges, the imperfections a secret. This dichotomy preoccupied me even when I was a mere twenty years old.

Tell me a bit about your family background. Did you have someone in your family who in some way influenced you to pursue a career as an artist?

There was no one in my family who would have been a sort of role model for me in that sense. My father, as it so happens, was illiterate. My mother could read and write, and though they were both day laborers, manual laborers, my mother had a longing for something else too, something that was not just physical work. She worked as a maid for some Jewish families. She even did cleaning work in the building which later housed the radio, where I went as a child actor. She told me about all the amazing books she had seen in those beautiful apartments, even a piano. She was drawn to that world. It captured her imagination. When she was a little girl, during the Great Depression, many people from Yugoslavia went to France as guest workers, and she had gone too, with her parents. I was quite amazed when she counted to ten for me in French. I remember the experience, how much I loved the fact that there was such a language.

I’d learned Serbian out on the streets, but the fact that there was a third language seemed almost magical. And then of course there’s the musicality of French. I wasn’t interested in what the words meant, only their sounds. I was actually living in a world of five languages. I didn’t just hear the minority languages on the radio. Our neighbors spoke several languages. The way in which this multilingual environment seemed so natural to me must have something to do with my move towards sound poetry. And besides, ever since I was a child, I had dreamed of being an actress, though I wasn’t much of an extrovert, and indeed for a long time, I didn’t even know what that meant. To get into the children’s theater group, you had to be able to speak well and read from a page. In 1953, the shows were still live. The first radio play I got a role in (they called me little Katy Ladik), was Uncle Tom’s Cabin. I played the part of the little girl with the tragic fate. Back then, everyone listened to the radio. There wasn’t really anything else to listen to, and anything said on the radio had the weight of a revelation. I became very popular among my peers. They held me up as a kind of example for the others to follow, because I was also an excellent student. This was something of a burden too, an obligation, because I always had to meet expectations. Before I turned twenty, I brooded a great deal over whether or not I would pursue a career as an artist, whether actress or poet. I would only do it, I thought, if I am more talented than average. If it turns out I’m not that talented, then I’d rather find some ordinary profession. And in order to make sure that I would actually be able to do this if necessary, I got a vocational degree in economics. I didn’t want to go hungry, after all, and a good job in some public office was a nice guarantee that I would always be able to make ends meet. I had a good salary as a bank clerk, and the possibility even came up that I would get an apartment. It seemed like a comfy existence: I would work, and from time to time, I would get a part in something, or maybe even write poems. True, but then I would have been an actress or a poet merely as a hobby. So I made a radical decision: I left my well-paid job, with its promise of an apartment, and went to work in radio for half the money. I felt that I could perhaps be more than just an average artist. I felt that I had the moxie and the grit, and I jumped into the deep water. I knew it was all or nothing, not something you could do half-heartedly. I knew I couldn’t be a weekend artist. I had to live the life of an artist with every fiber of my being.

Where did your interest in literature and poetry come from, and this realization that this was something you could only do in a radical way? When did you come into contact with this kind of poetry? What kind of people did you hang out with?

I wasn’t exposed to books in our home as a child. We simply didn’t have any books. At the radio, we were just given parts. We didn’t really have any kind of textbook. We suffered through the Hungarian reader book for three years, but it wasn’t in school that I acquired my knowledge of literature. When I was fifteen years old, I was given a book of poems by Attila József at the radio as a reward for my work. As a child, I had written playful, rhyming poems inspired by Sándor Petőfi, but as a teenager, I realized that this was not my world. If I had not gotten that book of poems by Attila József, I might have given up poetry, but his works helped me realize that there were other ways of writing. I felt like he and I were kindred spirits, since he had also come from a very poor background. And that was when I first came across free verse. But a few more years passed before I actually realized how to write free verse. It was during these years that I started going to the library. At first, I had no idea what to look for, what to read. I devoured literature indiscriminately, but even so, I still came across books that stood out. But I didn’t really hang out with people with whom I could have talked about all this. I wrote some poems when I was twenty. I came across a supplement to the magazine Ifjúság (“Youth”) entitled Symposion, in which I found works by Otto Tolnai, a poet who wrote free verse. I submitted some of my poems. They were very surprised and asked for more, and then they sent me a letter inviting me to come to the editorial office. I was dreadfully nervous, but they received me very politely (as a bank clerk). They mentioned Rimbaud and Baudelaire in connection with my poems, and I just nodded, for I had never heard of Rimbaud or Baudelaire, but I did then try to make up for my shortcomings as quickly as possible. Later, I often went to read more about the artists whose names I had heard. Naturally, French literature had an influence on me. I read more and more, and with more and more of a plan in mind, not as randomly and indiscriminately as at the outset. I only did eight grades of school in Hungarian. My literature teacher was a Russian woman. In class, we spent most of our time shucking peas for her, or sometimes she taught us to sew. Later, I went to a Serbian high school. So my basic knowledge of literature was spotty.

Later, the relationship to femininity, to your own body became important in your art. Where does this insight into your identity as a woman come from?

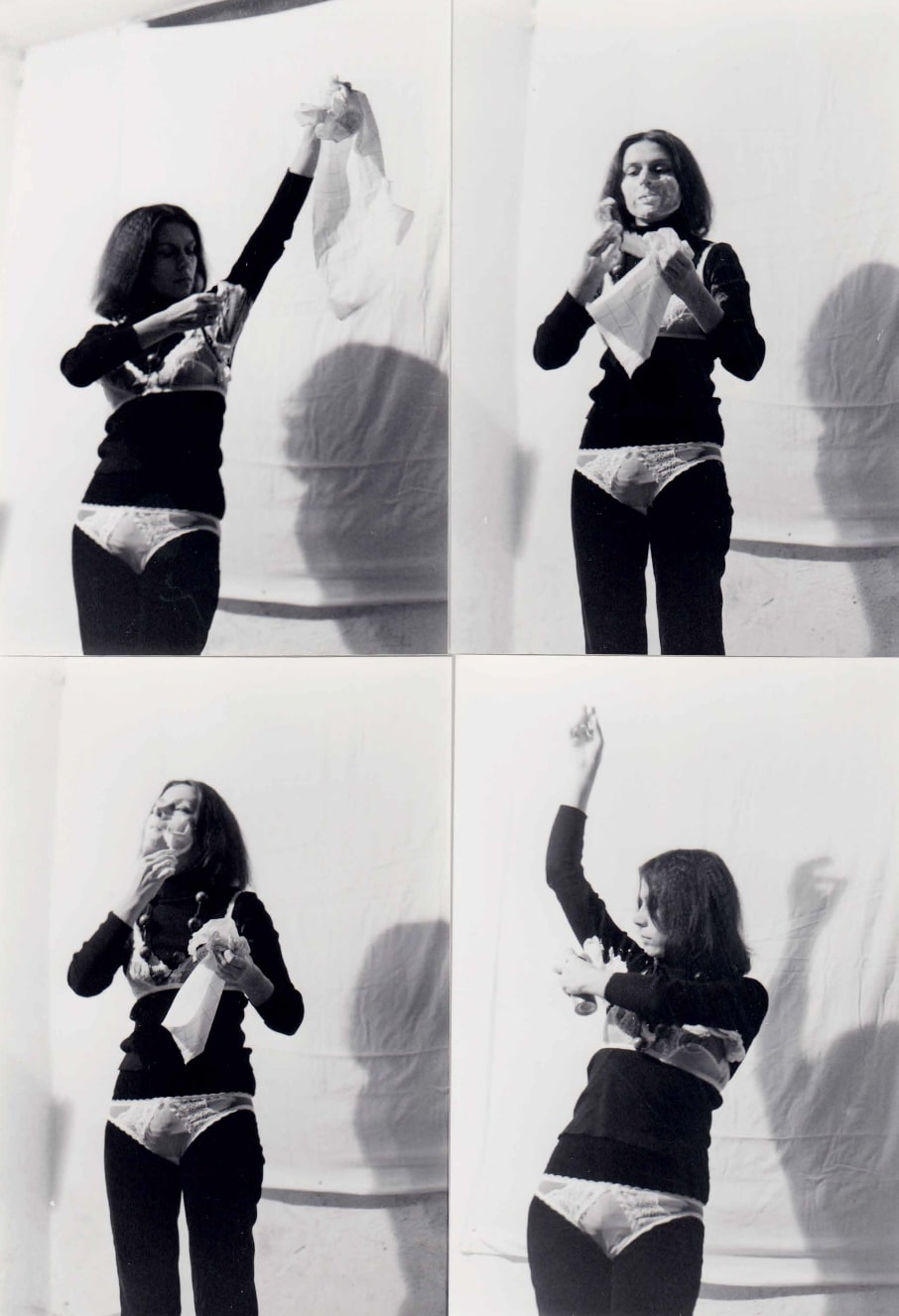

As an actress, I was not in the “beautiful woman” category, and I did not consider myself beautiful either. I did my hair in Juliette Greco’s Cleopatra style, and I wore either black dresses or turtlenecks, as if imitating the existentialists. I had an interesting look, but that was hardly to my advantage as an actress. At the same time, I didn’t want to be a bluestocking. It bothered me that when I went into the editorial office, the conversation immediately stopped, and they started flirting with me. They saw me as a woman and nothing more, or at least that’s how it seemed at the time, and after a while, I stopped going in. I had gotten married by then anyway. I had a child, and I was working full-time at the radio. I started lying low, doing what I could to minimize my femininity. For a few years, I didn’t really socialize. In 1970, at 29 years of age, I felt that my career as an actress and artist had come to an end, because while it was good that I was publishing in Hungarian in Vojvodina and had been accepted by the periodicals, I hadn’t had my own book appear until 1969, because what I was doing did not fit in to what was thought of as women’s poetry, women’s literature. Later, a theater company was formed in Novi Sad, and there were no works or roles in the theater’s repertoire that would have suited me. This was followed by a new period of crisis, and I had to find a way to break out. I decided to plan my own performance, my own podium, where I could pursue my art. I was thinking of performance evenings, but not in the traditional form of a poetry evening, where the poet or an actor elegantly declaims the poems. Even when writing, I felt that some of my poems were written to be read and some were works that I would want to read aloud. There are other poets who use exclamations like “ah” and “oh,” and the reader is left to interpret them as he or she sees fit, but I wanted to convey them as they had first taken form in me. As early as the 1960s, I had written texts that were intended for performance, performance scripts, concrete poems, visual poems, which were published in my 1969 volume Ballada az ezüstbicikliről (“Ballad of the Silver Bicycle”). Which also came with an LP! The seeds of all my later artistic genres can be found in that first volume. On my own stage, I did my own performances, and I also performed sound poems. I still create in these genres, but sometimes one of them comes to the fore. I write poems to be read, and I have exhibitions, not only of visual poems, but also of collages and objects. Sound poetry has remained a prominent part of my work, not to mention the performance genre. My discovery at the age of twenty that it is only worth pursuing art in a radical way, with unflagging commitment, and my decision to dedicate my life to art have determined this process as much as my aforementioned ideas concerning the frame. In the frame, you find the work of art, or my face, my body, which I present as a work of art, and there is life beyond the frame, the body, the voice, which are vulnerable. I often show the back of the work of art too, for instance in the case of the textiles, the back of the embroidery and the stitching. On one side, you see what we intended to show, on the other, the unsewn threads. That’s where you see the time that was sewn into the work. Time bundled together in the artwork. And this is relevant not only in the case of the objects that were made by hand. Time is also there in the poems. For instance, the effect that a poem has on the viewer as long as the viewer is still engaged with it. Whether the word in question has a semantic value or meaning or not. How long does an “ah” or an “oh” exert an influence? Does someone who hears it take it with them?

As early as the 1970s, I was interested in printed circuit boards The insides of things, the back. In radio, the microphone is the surface of things, and what the sound engineers do, that’s the back. I liked to watch them work, that’s where I discovered that they sometimes throw out these interesting little flat objects with drawings, with wires soldered on to them. They explained to me that these objects were printed circuit boards. I found them fascinating, because I could tell that they were from the inner workings of the machine, and they clearly contained knowledge and secrets. I collected them and took photographs of them, and then I projected them on the wall as part of an exhibition, and as if reading from sheet of music, I sang the diagrams, the lines, the dots: the “messages.” As I mentioned earlier, the mystery of machines, the unravelling of these mysteries has been a preoccupation of mine since childhood. A few years ago, I based my performance Alice in Code Land on this, since after all, we live in a world of codes. I’ve always been amazed by how much information you can squeeze into those tiny little black and white diagrams, barcodes, QR codes.

Tell me a little bit more about the milieu in which you were working when you published your first volume of poetry. Why, after so long, was it finally published? Who were you in contact with? Who was your audience? Who read your poems? When did you first see performance art? And when was your first non-traditional stage performance?

I was strongly influenced by the Belgrade International Theatre Festival, or BITEF, an international theater festival that was and still is held in Belgrade. In the late 1960s, they presented contemporary, avantgarde plays, including productions by underground companies from New York, and I realized that this was the world in which I wanted to move and create. My first performance in 1970 was a tremendous success, and I soon became popular. For the Serbs, I represented what the trendy New York companies were doing at the festival. I had never seen a performance at the time. I had only taken part in one happening, and that had been in Budapest. In 1968, I mixed with Hungarian underground artists, Tamás Szentjóby and Miklós Erdély, but there were also filmmakers and writers among us.

How did you end up coming into contact with them?

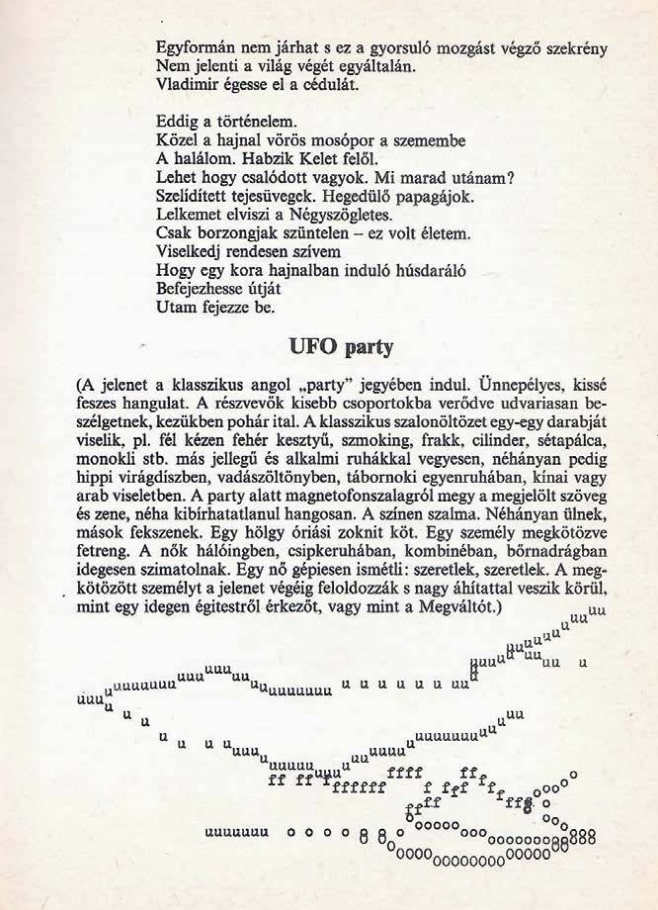

Szentjóby contacted me, by letter. As it turned out, I was cited as an example of what not to do in the official academic circles in Hungary, but the underground circles were in contact with Symposion, so after reading my poems, they contacted me through the editorial office. Szentjóby and I exchanged letters for a long time, but we didn’t meet in person until I was invited to the UFO, happening in Budapest, which later became very famous.

Tell me about your first performance, held in 1970.

It was more of a presentation than a performance. I was unknown in Hungary at the time, but I had done a performance in Serbian in Yugoslavia. I had no hopes of publishing on the far side of the border, in the motherland, in Hungarian. In the Hungarian world in Vojvodina, I was essentially an example of what not to do. I didn’t want to write in Serbian, so instead, I translated my poems with the help of Judit Salgó, and then I put together a repertoire of our translations that had been composed for recitation. In my solo show, after the poetry recitation, which was relatively traditional, I did poems in the form of a recitative, which was an indication that sound poetry was coming next. I performed my sound poems exclusively in Hungarian. This was followed by a short performance piece in which, garbed in shamanic attire, I did a kind of ritual. There was a touch of eroticism in it, and of course, that’s what caught people’s attention the most. Yet with this deliberately planned structure of the show, I wanted not only to acquaint them with the poems, but also to show, through the performance, something of my life’s journey. I printed out the poems and other poems of mine that had been translated into Serbian and distributed them among the members of the audience. I held this performance in several major cultural centers in Serbia. My poems were published, and soon, I had become very popular.

The shamanic ritual and then your 1972 Egyptian performance R.O.M.E.T. deal with the themes of death and the afterlife. Where did this spiritual turn come from? What inspired it?

I definitely see the multicultural surroundings in which I grew up as the point of departure, since this was a world in which I was always confronted with communication problems. In order for a message to make it through the gates of incomprehension, one would need a universal metalanguage. I sensed that rituals were capable of playing precisely this role in a community. It is not the meanings of the words that matter, but rather the sublimity of the ritual, the mysteries that everyone senses. This is what one should strive to create in poetry so that everyone can understand it. But then I wouldn’t call it poetry, but rather the conveying of a message. I sensed that there was a need for dramaturgy, and the lamentations and the rituals surrounding the coming of rain that I had experienced in the Serbian world around me were the inspiration for this.

I remember how the man dressed in green leaves, Dodola, by the pagan mythical name, would come down the street in dry summers dancing and singing the ritual rhymes. Everyone ran out to watch, and we all felt the same thing, we were all swept up by the same spirit. This was the kind of effect I was trying to achieve. I felt that one needed a kind of vocal technique for poetry that was not the same thing as recitation or song. I had studied folk music and literature to learn about the role of a shaman in a community, and I had come to realize that the poet has precisely the same role, because both the shaman and the poet are mediums. The goal, with my poetry, is to take a message to the highest plane of existence (what in Hungarian we would call the “seventh branch” of the tree of life) and to return with a response. It also has a role as something that brings people together: my creative message, garbed in the dramaturgy of ritual, which was also about femininity and how to live it. After my performances, many people—especially women—have said that they felt that they had a bond with me. At the time, it took a great deal of courage to present oneself like that, to accept and show one’s body as a woman. To say, “I am here, shoot in this direction,” knowing that I am vulnerable. And the critics were not merciful. They scoffed and sniped, especially the Hungarians.

I wanted to use a metalanguage that everyone would be able to understand. I would recite my Hungarian poems in front of Serbian audiences, but they still sensed exactly what I was trying to convey. I was thinking in archetypes back then. I wanted to express pain, defiance, and anger, but fertility rites are understandable to everyone. I performed them all over Europe, and I was never confronted with looks of incomprehension. The musicality of the language, the sound effects were the key which enabled everyone to hear the message. What I was doing was authentic. I didn’t want to follow the trends or do what the beatniks were doing in Western Europe or America. I couldn’t fight against consumer society because I was waiting for us finally to have a surplus of goods. Way back then, we were already washing the nylon bags that are trendy today so that we could use them again. I had other problems. First and foremost, that I was a woman, and so I had to figure out how, as a woman, under pressure to play traditional female roles, I could, while working, be successful as an artist. I didn’t get much help, no organized childcare, no readymade meals, I had to manage my time and my energy five times more attentively to be able, alongside everything else, to create. And in the art world, I had to fight a lot harder to be able to write differently or to show my body as a poet, if that was the best way to get my message across. I didn’t have a problem with that as an actress. Different rules apply to a poet. It even became an issue for the communist party.

People in the party may have been scandalized, but to what extent was all this accepted in the artistic circles in which you moved, or abroad? In the exhibition where we are sitting, there are examples from the region of female artists using their bodies in performances, with face painting and the like.

In the 1970s, in the former Yugoslavia, Marina Abramović and I were the only ones who put our bodies on exhibit as art objects, admittedly in different ways. It wasn’t forbidden, but it certainly caught people’s attention. The Slavic audiences had a more positive, curious approach. The Hungarians from Vojvodina, however, were quite outraged. They used the label that I had been given in Hungary, “naked poetess.” A poetess, after all, should remain in the background, garbed in black wearing glasses, ugly, and, if possible, with her head covered.

Who were you in contact with at the time? What artists’ groups and institutions? We know about how you and Abramović met the prominent representatives of the Hungarian avantgarde, but what ties did you have to artists like this from Vojvodina, for example?

I knew people who were active in the Yugoslav avantgarde, and they knew me, although I was still independent at the time. The Bosch+Bosch group was a significant presence, and I became a member when Bálint Szombathy and I got together and married in 1973. But the roles were divided based on gender. The men had the visual part, and I was only active in works having to do with sound. It was not a long-lived collaboration. Slavko Matković and Bálint Szombathy, the founders, brought it to an end in 1976. After the group had been dissolved, we had more and more exhibitions in which I continued to take part with sound poetry works. My visual compositions did not fit in with their macho vision. They were too “feminine.” I was already working with patterns at the time. I didn’t care about trends. I wanted to remain true to myself. For me, this was everyday life. I was compelled to sew, for instance. I wanted to show, to transform what constituted my own life. I made collages using patterns, to which I gave voice, which I sang at exhibition openings. But this didn’t really capture the group’s interest. We also had a joint exhibition in Hungary. The first time, we performed at the chapel exhibition in Balatonboglár, to which we had been invited by Gyuri Galántai and his circle. But I was very happy to work with Janez Kocijančić in Novi Sad. We did a performance together, embalming the pharaoh, in which I played a priestess to refer back to the ways in which rites appear in my work. I was also very glad to perform at sound poetry festivals with Endre Szkárosi. I worked a lot with him and Zsolt Sőrés even before I moved to Hungary.

What prompted you to leave Yugoslavia and settle in Hungary?

I had never thought, at the time, that I would ever have any chance of publishing anything in Hungary, especially since I had become an example of something to be eschewed in the university teaching materials. Dr. Béla Gunda, an ethnographer from Debrecen, was the first person to respond positively to my work. He wrote a paper on my folklore-inspired fairy tales in the early 1970s. It was published in German in Fabula and in Hungarian in Új Symposion. He compared my poems to paintings by Chagall, where folklore roots mix with surrealist elements. Imre Bori, a literary historian from Vojvodina, began to suggest that there was poetic value in what I had written, and he was followed by others. This opened the path for me. It wasn’t until the mid to late 1980s that I was first asked for manuscripts in Hungary, when I was in my late forties. By then, my name was known all over Europe, and I was regularly invited to sound poetry festivals. My poems were not translated into other languages. Considering the genre in which I was composing, that wasn’t necessary, and indeed I could not have achieved what I did in other languages. I was not planning to move to Hungary. I felt confident in the milieu in Yugoslavia. I was very able to express myself there, but then in 1991, the war broke out, and I didn’t really have any choice. The Yugoslavia in which I had grown up suddenly ceased to exist, or rather fell apart. The country was atomized. It was banned, as were its citizens. We were not able to travel, though I was at the height of my career at the time. My son was studying composition at the Music Academy in Budapest. I knew he would not come back, since he would have been immediately drafted and sent to the front. Young people were fleeing across the border in large numbers. My room for maneuver had become so limited that I didn’t really have much choice. I joined my son in Budapest. I began my life anew in Hungary. It took a few years before I felt like I would be able to continue where I had left off in Vojvodina. I began writing and publishing again. This was in the period following the fall of the socialist regime. The doors at the editorial offices of the journals were swung open for me. I got a Hungarian passport, and after a break of some four or five years, I was able to travel again. Art historians at the time were discovering that in recent decades interesting things had been happening in Central and Eastern Europe too. The museums and curators who approached me were interested in the avantgarde movements of the 1970s. They were collecting works of art and photographic documents. In 2005, I was discovered as a visual artist, and people began to show some appreciation for my visual and performance art, which is how I came to be known as an avantgarde performance artist.

Did you bring all your materials, photographs, and documents with you when you moved to Hungary? Why did you even hang on to them in the first place? You could not have known that they would later be valuable.

Naturally, I never really expected any of those things to have any artistic or, much less, monetary value, but I was always under this kind of pressure: so busy, always wrestling with a lack of time, that I never had a chance, while managing my work, family, and creative activities, to organize my life. I also moved several times, and I never had a chance to go through my things and be selective. I would grab a desk drawer, dump the contents into a bag or a box, and take it all with me. I often thought, when I was staggering under the boxes, bags, and sacks, that I should throw it all out, but I never dared, just on the off chance that there might be something important in one of them. But I didn’t have the time or energy to start going through it all. When the curators came, I had no idea what I would find in which bag. We started rummaging through them at random, and I slowly got some grasp of where I would find things from a particular decade or made with the use of a particular material. I moved again not too long ago, and all my stuff, which I was beginning to manage to sort out, is now a chaotic mess again. I don’t like to move, but somehow my life has always taken twists and turns that have forced me to. In my works—and therefore in my life as well—transformation has always been one of the main motifs. In my personal life and in my art. In fact, I often make changes to my sound poems and my performances, but I don’t rewrite my poems once they have been published. Jenő Balaskó, for example, with whom I did the aforementioned literary evening in 1970, rewrote his old poems in the 1990s, which in my opinion is regrettable, and I am not the only one who thinks this. I would never do that. My poems are imprints of my life, of the feelings that I embrace.

Your career has soared, and you may never have expected to attract so much attention. Does being in documenta in any way change your assessment of your oeuvre? Have you reevaluated it? Do you see the works that you made in the 1970s differently now, or do you still consider everything that you did and do as subordinate to your poetry?

When people ask me what I consider myself—and they do, they ask whether I see myself as an actress, a poet, a performance artist, or a visual artist—I always have the feeling that they are overcomplicating things. If I had to give a simple answer, then I would say I am first and foremost a poet who tries to push the boundaries of poetry. The shaman is a poet of sorts, the embodiment of a vision and the bearer of a message. The poet also has something to say, which she is usually expected to convey in written form, but for a long time now this has not been the only way. There is visual poetry, sound poetry, gesture poetry, which is close to movement theater, which is also a breakoff from a classical form that is limited to the extreme, namely ballet. Movement theater is also a free genre, where you are free to make ugly movements, and you don’t have to smile all the time. For me, poetry is a genre where everything is permitted: I can express myself using my own body, my own voice. If I use a costume or some implement, I do it to defend myself, because I am very vulnerable. Or I do it because it helps me cross a boundary, like the shaman’s drum helps the shaman. I relate to an umbrella or a piece of cloth as a partner. I breathe life into it, I tell it my most closely guarded secrets. My performance is not a monodrama, I don’t say what I have to say directly to the audience (it might seem alarming or aggressive if I were to say it to someone’s face). Rather, I say it to my transcendental “partner.”

A brief biography

Katalin Ladik was born in 1942 in Novi Sad. She pursued studies at the College of Economics in 1961–1962 and then trained as an actress at the drama studio in Novi Sad (1964–1966). She began her literary career in 1962 while working as a bank clerk. She worked for Radio Novi Sad from 1963 to 1977. In 1972, she joined the company at the Novi Sad Theater. She also appeared in films and TV dramas. She worked as editor of the poetry column for Élet és Irodalom in 1993–1994 and Cigányfúró in 1994–1999. From 1993 until 1998, she taught at the Hangár musical and theatrical education center. In 1992, she moved to Budapest, and over the course of the past 20 years, she has lived and worked alternately in Budapest and on the island of Hvar. In 2017, she was invited to participate in documenta 14 in Kassel.

This text is an edited version of a video interview with Katalin Ladik held on 15 October 2021 as part of the exhibition Poetry and Performance: The Eastern European Perspective. The interview was done by Tünde Topor. Video by Marcell Esterházy. Thanks to Renata Szikra for preparing a typed version of the interview. The full video version is available at Artmagazin Online. © Artmagazin