Machines Beyond Phantasmagoria

On Tamás Waliczky’s Imaginary Cameras

The Hungarian Pavilion at the 58th International Art Exhibition of the Venice Biennale features the work of new media artist Tamás Waliczky: images of cameras that have never existed. They have been retrieved from the domain of virtual reality to answer the unhistorical question of “what if?”, at least as far as the history of visual representation is concerned. Not incidentally, the author we have invited to write about this is a speculative design researcher.

“Machines are simulated organs of the human body.”[1]

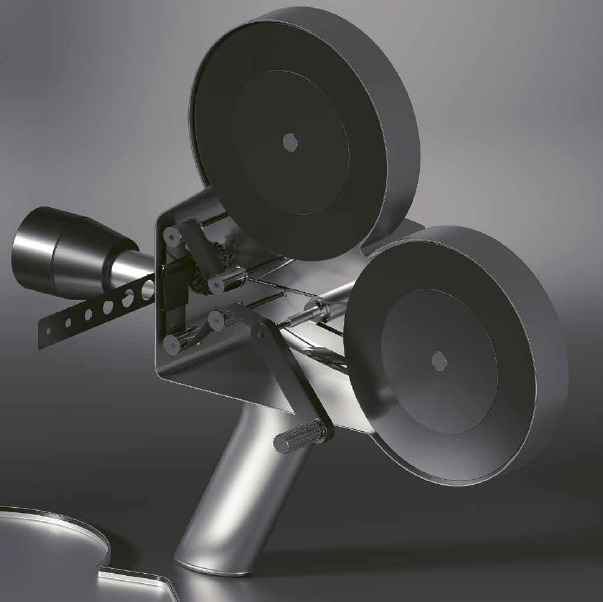

Tamás Waliczky simulates the parallel courses of technological progress; our image of the world could be entirely different from what it is today – his Imaginary Cameras merely visualise the devices required to produce these images, but not the results of photographic representation. The focus is on images of machines. We are viewing things meant give view.

Fiction and thought experiment, but not without stakes: “machines are simulated organs of the human body” – goes the motto above –, and technology provides not only the means but also the framework. The camera allows for, and also defines, the course of a new type of vision. We know, since Marshall McLuhan at the latest, that our devices rewrite as much as they extend us. Radical technological development at once entails the reconditioning of the body and the corporeal experience. “All media are extensions of some human faculty – psychic or physical” [2] – we keep repeating the mantra, and indeed: if, say, we had adopted Waliczky’s Spiral Camera as a standard, perhaps we would be sitting in front of a circular cinema screen today instead of a rectangular one. This is not a marginal question. Our designed environment and machines fundamentally determine the course of our thinking and imagination: they enable, they allow.

We are “embodied in an extended technological world” [3] – as Robert Pepperell puts it. In fact, this is a world the material of which we are in constant engagement with, and yet we usually fail to comprehend the way it works. We use our digital devices but we cannot see inside them; underlying human-centered design, the functionality and comfort of good design, the seamlessness of interfaces, some internal mechanism is clattering away, of which we have zero knowledge as everyday users, nor do we wish to. To use Vilém Flusser’s term: we are surrounded by “black boxes”. Our technological devices conceal their internal mechanisms. I am using my smartphone on a daily basis, and yet I have no idea about either how it works or the global communications infrastructure it is integrated into while connecting me to it. In this sense, the user interface is something that masks something else. We are comfortable being strangers in our own world – which is a serious design problem.

Tamás Waliczky is absolutely aware of this, and his work at the Hungarian Pavilion of the 58th Venice Biennale elegantly opens up new perspectives. He creates designs of machines that, instead of concealing their mechanisms, reveal and allow us to understand them. If you will, Waliczky offers us twenty-three anti-“black boxes”.

And in order to do this, he must take recourse to the already antiquated world of cameras, which might arouse suspicions of technological romanticism, except there is something fundamentally humorous in it. A temperate irony, which is not apparent at first glance because of the precise representation and the attitude of an engineer. After all, these are digital renders of analogue devices, and it must not be incidental that Waliczky did not manufacture 3D prototypes of his imaginary cameras. The machines remain images – software-generated predigital visions that pillory the computer itself along with other devices of digital image-making.

Theodor W. Adorno refers to artistic practices, the essence of which is concealing their underlying mechanisms in order to achieve a more effective illusion and deeper reception, as phantasmagorical. [4] This concealment is not necessarily conscious: whether we examine contemporary photography or new media art, we will see artists readily using the technical devices required to create artworks, while being oblivious to their mechanisms and having limited access to them. The circuitry magic that takes place in the background is usually invisible to the artist, who only accesses its result or interface. The artist is confined to the space marked by the technological status quo.

Conversely, Waliczky’s cameras go beyond the realm of phantasmagoria – while they themselves are the products of imagination. They pose the question: what if? To what extent would we see things differently if at this or that fork in the history of photographic devices we had taken a different road than what is known today? What Waliczky’s Imaginary Cameras represent is speculative design at its best. And a peculiar version of it too: instead of looking into the future, it contemplates the past – carrying out what could be termed as imaginary design archaeology.

In the spaces of various media and design labs, speculation is typically enthralled by the future. In these fields the speculative basic stance bears a promise: “Inventing the future!” –Jussi Parikka cites MIT Media Lab’s slogan from the 1980s. [5] Then again, why would proposals for “inventing the past as well as inventing alternative timescales” [6] not constitute a similarly legitimate approach? Imaginary Cameras experiments with fictitious temporalities along exactly the same lines, while remaining devoid of banalities attached to technological innovation. In institutions at the forefront of design research – such as IDEO, Carnegie Mellon School of Design or the aforementioned MIT Media Lab – developments in the experimental phase are characterised by reverse engineering and “technology brokering”. [7] However, Waliczky diverts from this designer model: he abstains from deconstructing our existing devices, unpacking technological “black boxes” or speculating on innovations of uncertain outcome.

Instead, he opts for a new point of entry; he takes recourse to the dawn of photography in the 19th century, he fills his research lab with early tools of analogue imaging, and builds his own machines amidst this scene. He thus also creates a new timescale, as “[a]n invention of a technology (new or existing) is always an invention of a particular temporality.” [8] His machines relate laconic stories on the frontier between imagination and reality.

The presentation of Imaginary Cameras in Venice was a turning point not only in terms of Hungarian new media art, but also from the aspect of endeavours in speculative design. Tamás Waliczky’s consistently experimental work deserves our attention in its own right, because it allows us to conjecture such areas for the discernment of which we would have to invent new tools first.

Tamás Waliczky: Imaginary Cameras, Hungarian Pavilion at the 58th International Art Exhibition of the Venice Biennale, until 24 November 2019

Ákos Schneider is a researcher in the fields of speculative design and posthumanism. He is assistant professor at Moholy-Nagy University of Art and Design and postgraduate student at the MOME Doctoral School. He was on the New National Excellence Programme scholarship (ÚNKP, 2017–2018), engaged in the fields of design and art research, following which he was a guest researcher at the School of Creative Media of the City University of Hong Kong (2018).

| 1 Flusser, Vilém: The Shape of Things: A Philosophy of Design. London, Reaktion Books, 1999 [1993], 51.

| 2 McLuhan, Marshall – Fiore, Quentin: The Medium is the Massage. Gingko Press, 2001. [1967], 26.

| 3 Pepperell, Robert: The Posthuman Condition: Consciousness Beyond the Brain. Bristol, Intellect Books, 2003, 187. “Humanists saw themselves as distinct beings in an antagonistic relationship with their surroundings. Posthumans, on the other hand, regard their own being as embodied in an extended technological world.”

| 4 In his 1952 book, Adorno writes about phantasmagoria in regard to Richard Wagner’s endeavours to conceal the orchestra during the performance and thereby achieve a higher level of immersion by the recipients. (Adorno, Theodor: Versuch über Wagner. Berlin, Suhrkamp Verlag, 1952)

| 5 Parikka, Jussi: The Lab Imaginary: Speculative Practices In Situ. In: Across and Beyond – A Transmediale Reader on Post-Digital Practices, Concepts, and Institutions. Eds.: Ryan Bishop, Kristoffer Gansing, Jussi Parikka, Elvia Wilk. Berlin, Sternberg Press, 2006, 78.

| 6 Parikka ibid.

| 7 Technology “brokering” stands for a designer attitude wherein the solution of development and design problems is expected from free experimentation with emerging technologies, as well as creative engineering and imagination. Design research in this approach is characterised by an experimental trial-and-error method instead of reasoned consideration. In response to this, in recent decades, universities and design firms have established technological playgrounds or “sandboxes” where the course of research and development is dictated by designer speculations instead of the desire for scientific proof. (Koskinen, Ilpo – Zimmerman, John – Binder, Thomas – Redstrom, Johan – Wensveen, Stephan: Design Research Through Practice: From the Lab, Field, and Showroom. New York, Morgan Kaufmann, 2012)

| 8 Parikka, Jussi: The Lab Imaginary: Speculative Practices In Situ. In: Across and Beyond – A Transmediale Reader on Post-Digital Practices, Concepts, and Institutions. Eds.: Bishop, Ryan – Gansing, Kristoffer – Parikka, Jussi –Wilk, Elvia. Berlin, Sternberg Press, 2016, 81.

Translated from Hungarian by: Dániel Sipos