The Designer Is Like a…

Interview with Gábor Palotai

In the very same room where he was told his thesis received the grade 2, years later he accepted an honorary professor. The internationally renowned design expert with numerous awards lives in Stockholm; he considers the design and the prototype of an applied, reproduced work pieces of art, just like a painting. Being someone who creates objects, he prefers the constructed environment to nature, and he surely has seen the movie Gladiator.

Artmagazin: Where were you born and what was your family like?

Gabor Palotai: I was born in Budapest in 1956. My mother, Éva Németh is a textile design artist, my father attended the directing course at the College of Theatre and Film. After I was 6, my mother raised me alone. This was quite unconventional in 1962, we were distinct even among our fellow tenants, both in Óbuda with my grandmother and in Váci Road, where my mother purchased a flat later. The latter was a peculiar setting, a pure working class neighborhood, but Attila József Theatre was there, too; the actors of the theater and our teachers at school were declassed elements, in exile, so to say. There were contrasts, thanks to classmates with apparent features of the 13th district. When I was in the 7th grade, we moved to Frankel Leó Street. I continued my education in Rákóczi Secondary School, in a good, unified class; it was here, where I became friends with László László Révész, who was a classmate of mine. All in all, this period was a golden age to me.

I belonged to that milieu so much, what I wanted instead was to distance myself from it. My mother took me to gatherings, to exhibitions, and during summer to art colonies. She knew everyone: the Erdélys, or Mariann Szabó (from the textile scene) and her husband, Imre Makovecz; as a child I was very familiar with this milieu, yet, I had no intention whatsoever of becoming involved with textile, for example. During the first years at secondary school, I didn’t even think about it, but then came the pressure. My mother made me practice drawing at home, and to test me, she arranged a still life with flower. She was satisfied, so she made me take drawing classes ; at first night classes at Ipar Secondary School, then in Fő Street; there I started to gather a notion of consciousness, a fascination toward art, and not because of my friends, but particularly because of drawing. Drawing changed my life, it opened up so many things. Nothing became a something, I became someone, too, by being good at drawing. I had thoughts, I understood films and poems better. After high-school graduation I was accepted immediately to the College of Arts and Crafts, which offered a specialist training course, although not exactly the kind I had in mind. Nobody really cared about what I wanted to do, what I wanted to become; it was about copying our teachers and accomplishing design and typography tasks.

Who were your teachers?

It was incompatible with what I brought from home. The one mentor I had was at home… My knowledge regarding the profession might have been limited, my aesthetic sensitivity and my judgement, however, worked just fine.

My mother has an outstanding oeuvre. Her sense of forms and colors has always been excellent. She was a student of Ernő Schubert at the College of Arts and Crafts. After graduating, she found a job—as was expected of her—, but she became a freelancer a few years later. Her career as a textile designer began in the 1960s; she became a true designer, and, unlike most of her contemporaries, she resisted the artistic tendency popular in textile at that time. Instead, she became a designer, she ordered the production of her designs from a handmade-quality carpet manufacturer in Békéscsaba, which mostly made weaved or knotted carpets for export.

We have some of the later series; back then these weren’t archived. Following the regime change, the factory was reorganized, closed, sold; lots of the things went missing, just like everywhere else. Those were confusing times in Hungary, lots of things were lost in the joy of freedom; designs, intellectual productions… Nowadays, Hungary is more of a wage worker country, busy with the production of someone else’s designs, and not with the export of its own thoughts. We don’t have an influence over the future, because—unlike Sweden, Italy, or Finland—production here is not based on domestic designs. It is up to the client to decide when the production is terminated.

She is not. Her latest solo show was in the Dorottya Street Gallery in the 1980s, Miklós Peternák gave the opening speech. My mother participated several textile biennials then, yet, instead of “space textile,” it was the design that fascinated her. This is what my hinterland was.

What about your father?

I do look like him, however, our relationship was broken, he was not present in my life. I didn’t feel his absence, my childhood and my youth was beautiful and unrestricted.

The college was an elite institution, out of the hundreds of applicants only 5-6 were accepted; yet, the education we received couldn’t have been considered contemporary. Those times were the highlight of Kraftwerk, punk, or concept art. Everything that we talked about, that fascinated us, came from the outside; these influences weren’t allowed into the college. New Wave, New Order, the graphic approach it brought were renewing traditions. It would have been possible to achieve this at the college, too; to assemble something up-to-date from the historical pass. I remember it very clearly what I felt when I went abroad: everything became up-to-date all of a sudden. What I learned at the college—as boring as it was—became useful, valid, even intriguing, once put in a different context; this applied to architecture as well as design.

Discovering concept art was one of those major experiences that embodied a fundamentally different approach, aesthetics.

Stuff from drawing classes, graphic designs, collages, even photographs. Mostly documentary pictures following the aesthetics of the time. The two shows were pretty successful, though without any risk. Getting back to inspirations: the Eötvös Loránd University held a series of screenings, every Thursday, going through the history of film; maybe two movies at a time? Movies by Godard, Bergman, and Kurosawa made a big impression on me.

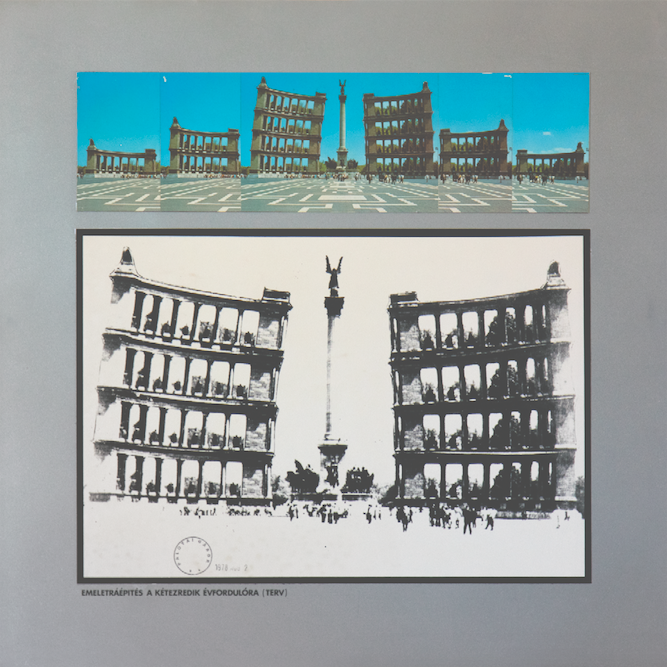

I had friends, but was busy with the college, I wanted my works to have a shocking effect. I wanted them to be different, harsh, to make the viewers lose their comfort. At the beginning, the point was merely to execute the tasks; with photography, which evolved into collages, however, it became art. I created the collages using my own photos most of the time, with a few reproductions occasionally, accompanied by postcards I purchased.

After leaving the army, I went to Poland with Miklós, where we saw several unbelievably exciting concept art exhibitions, for example in Cracow. The art scene there was much more advanced than in Hungary. We visited the Venice Biennial as well, with a tourist passport; the major experience of the biennial was the large, expressive painting style coming from Germany.

My true inspiration in the 1970s was, however, when I spent one month completely alone in Paris, after my first year in college. I will never forget my experiences there. That year, 1977, was marked by the opening of the Centre Georges Pompidou, under the direction of Pontus Hultén, who curated such exhibitions like Paris–Moscow two years later. The building itself is an exemplar of Postmodern architecture, and it seemed impossible and pointless, or disappointing, to return to the college after seeing this exhibition and perceiving how different cultures are interconnected and affect each other, after learning about all the streams and the links. I made further trips to Paris, for example in 1984, when Café Costes, designed by Philippe Starck, was opened; the approach, the kind of aesthetic sensitivity I encountered there astonished me once again. The way Starck integrated the facade clock, familiar from Budapest Keleti railway station, into the interior, to mention one thing.

What were the notable exhibitions of the time in Budapest?

When and why did you leave in the end?

My career at the college was coming to an end, so to say; I felt that several of the teachers were after me. Maybe my unfitting works triggered the conflict. Close to the end of the fourth year, I received the special award from the international board of the Graphic Design Biennal, which was annoying to my teachers; after this, I did have numerous enemies.

It was a small, printed notebook; a photo sequence of me jumping into a box, and then the box is opened and it’s empty, I’m gone. It bore the look of concept art, its title (Talán eltűnök hirtelen, [I May Suddenly Disappear]) was a quote by the poet Attila József.

I had one more “scandal” back then: I displayed posters in the exhibition space of the Hungarian Academy of Fine Arts; the posters said “I am not exhibiting.” Many expressed outrage, I heard that some students there were threatened to be fired because of this. Eventually, the news got to the college and it didn’t made people happy. It was a rigid world. For example, they shut down the darkroom for years, saying it needed to be renovated, only to stop us from making photographs, which they thought to be pointless. I fabricated my own darkroom at home in the basement, and worked there.

Anyway, I made it till graduating, my thesis defense, however, turned out to be an actual trial. At the other end of the long table sat the teachers next to each other, facing me. There was no conversation, they just announced the “charges.” My diploma work comprised book designs, posters, photographs. I installed a long line of book pages in the manner of a comics on the wall, including Kafka’s The Burrow, Béla Hamvas’s Tibeti misztériumok (Mysteries from Tibet)—one of the posters, for example, depicts Miklós Peternák playing chess with Death. (This was an homage to Bergman’s Seventh Seal.) The book was entitled Where Do We Come from, Who Are We, Where Are We Going?

They weren’t brave enough to accept this world, yet, they were too coward to fail me. They gave me a grade 2, which was quite rare; with that you didn’t receive a Fine Art Fund membership, which was a requirement for legal work in Hungary then. Every work of art was evaluated and needed approval. This seems absolutely unbelievable today. I realized this is not how I want to spend my life, especially not as part of this scene. After graduating, a gallerist approached me to make an exhibition in Stockholm. So, I didn’t return to Hungary from there.

How did your mother react to your decision?

I applied to the Swedish Royal Academy and to a design college (Beckmans Designhögskola) at the same time; I was accepted to both immediately.

How did you get along, did you speak Swedish or English?

I didn’t speak Swedish yet, but I did speak English, thus the language used for the consultations in my class was English. They very awfully helpful. A year later, at the design college, everything was in Swedish.

Did you have any income? How did you finance your studies?

I received a state support as a dissident. Because, following the exhibition, I just stayed there. The law at that time said that one became a dissident after staying abroad with an expired visa for more than a month, which was a crime. The police did visit my mother to collect my papers. There was a fight, my mother sent them off, later, however, she always faced difficulties when travelling. I was allowed to visit only after four and a half year; between 1986 and 1989, travelling between the two countries required a visa. I applied for visa to Hungary more times than to anywhere else in my life.

I was accepted to a two-years program at the Academy of Fine Arts there as a visiting student, because I had a degree already. It was a very good experience; the things that were disapproved at home, the things that were considered bad, those were the things that were endorsed out there, it was the other way around. In 1983–1984, I attended the final term at the design college. This was important for assimilation. I spent my first three years as a student, and with the help of a student loan—that I had to pay back later—I managed to sustain myself. Meanwhile, I had a job, too. When I graduated from the college, I received an offer from an advertising agency. Also, I right away joined a competition for young designers; the competition was announced for the first time, and I won. That made me somewhat recognized and helped to start my own career; the agency I got into was excellent, but it went bankrupt after one and a half year. After that I worked at a large design management company, my commissions multiplied, I had tons of work; eventually I outgrew these jobs and I established my own studio.

I launched Gabor Palotai Design in 1989–1990, and I’ve used that brand ever since.

What kinds of commissions did you receive with your own agency? What did you specialize in?

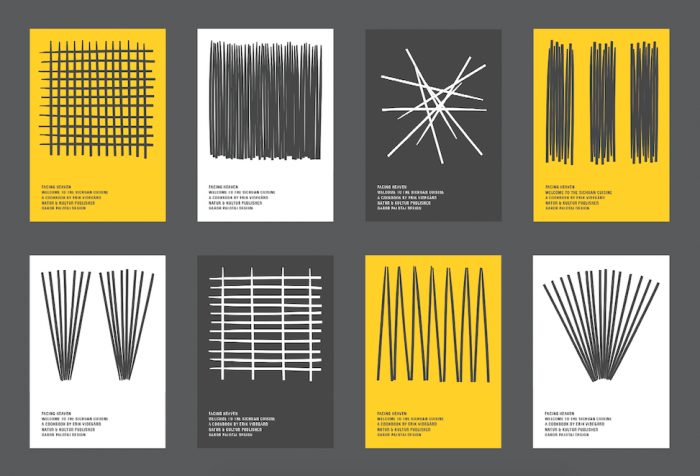

I had tasks regarding several aspects of visual communication, whether a visual brand language, a book design, or an object design. I’ve had art projects all along, too; art books, graphic designs, exhibitions, etc. Graphic design and visual design are, as far as I am concerned, art. This was my opinion already in the first year at the college, and this is what my opinion is today. A logo, an object, or a book has to be a work of art, too.

What did you learn thanks to your commissions? Is it difficult to accomplish your own ideas in Sweden?

It’s difficult and easy at the same time. The design market is as problematic as the art market. Clients usually have no idea whether how to purchase, commission a design. Apart from a few exceptions, every time we need to start from the beginning, explaining, defining what we’re talking about; and this has nothing to do with being a newcomer or an esteemed, professional designer. A good design is not merely proper in function, it is distinct from everything else of the same function, it embodies something additional. The client doesn’t realize this added value every time, it is often only fellow professionals and theorists who are able to recognize what makes a design outstanding; this is true of the client only retrospectively, when the design wins a prize, mostly. Taking the risk is one of the most crucial features of a designer, if you ask me; of course, going too far can mean losing the commission. When you enter the arena, you don’t know whom or what are you about to face and what you need to do to convince him/her in order to ensure the realization of the design, of the work. You need to construct a diamond formation that fends off every attack. Even if there is no way to prepare for a particular task, one needs to tend and cultivate the talent, the ability of problem solving. The profession has to be redefined every time; this is not an interest of the client, but the duty of the designer.

In Sweden that was the beginning of the Postmodern era. In the early period I found inspiration in Peter Saville’s works, in the album covers he did for Joy Division and for New Order, raising the relationship between image and music to a new level. Galerie Bruno Bischofberger appeared on the back cover of Artforum for many years, always with a view of the Alps: peasants, lambs, and the gallery’s name. Thus, a picture originally unfitting got into a new context, gained a new meaning. This was the means Saville employed as well; he rediscovered and brought the fonts used in “boring” books back. He used book typefaces on album covers, reaching back to Jan Tschichold’s influential work from 1925, The New Typography. (Other than this classic book, Tschichold designed the typeface for Penguin Books.) Apart from recontextualizing, the way the old is integrated into the new (and the other way around) is also interesting in all this.

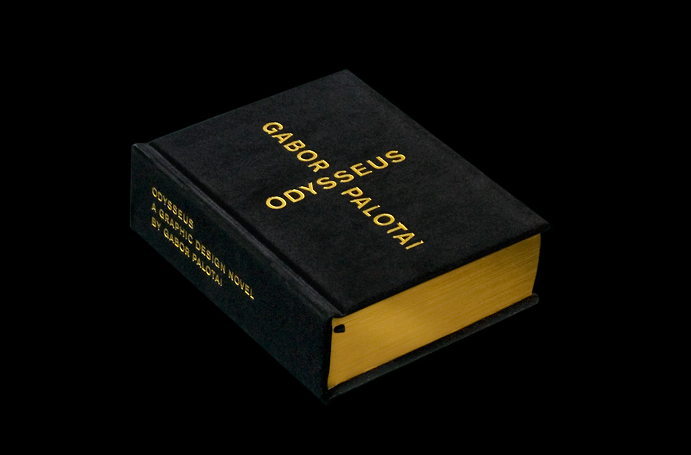

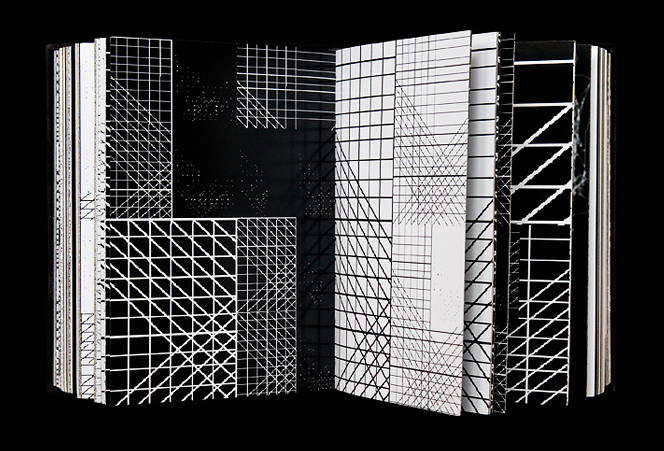

I don’t know whether prizes correspond with importance. Anyway, to me, the most important work is my book Odysseus. In Maximizing The Audience, which I made before Odysseus, I summarized my oeuvre until then. And I’d like to mention the 111 posters I published in the book 111 Posters. AM MU NA HI (American Museum of Natural History) is also very important to me; it comprises photographs of mounted animals from the Museum of Natural History in New York.

Could you tell more about that?

To me, there is no nature, only culture. In Sweden, however, everyone is obsessed with nature. To them, a forest, a lake, the landscape is an extraordinary phenomena, because there are no people, one can be alone in the quiet. I think the opposite: my nature is the park, a man-made piece of nature. This applies to animals, too. I’ve always been fascinated by staged animals and dioramas in the Museum of Natural History in Vienna or in Budapest. In Vienna, there are long cases and containers with at least a hundred different species of monkeys, all installed in various postures, and at least 500 birds are sitting on the shelves. Where I like meeting nature the most is in museums, at exhibitions. That is nature in a clarified, outlined form. If I go out into the wild, real, living nature, I’m always annoyed by something; the calling song of tricklets, the bugs, it’s cold or it’s too hot, etc. Once, I saw lots of mounted animals in the basement of the Royal Academy of Art in London, this is why I visited later the museum of natural history—with its nice, cool climate even in summer—in New York. Presented nature, in which animals, installed in front of painted backgrounds, can be heroes, like the characters at the Borodino Battle Museum Panorama in Moscow; I find this more exciting than real nature.

In Paris, the Jardin du Luxembourg was my favorite, that is my ideal; I like St. James’s Park as well, although it has a completely different atmosphere, being an English garden, with animals and a quite natural look, in spite of the fact that even the leaves are part of a master plan. The park depicted in the movie Last Year in Marienbad is also hard to forget; the French formal garden with a bench in the middle, where you can have secret conversations. Places like this allow intellectual things to happen, while the wild is about survival, struggle. What I’m saying is that city parks are my milieu.

What else do you enjoy? Are there further things that you let in? How do those influence you?

When thinking about my works, I’d use the term “Interdisciplinarity,” no matter how outdated it is today; nowadays things merge into one another, borders become blurred, all the genres and styles are present side-by-side. The designer is like a DJ, creating something new by mixing the motifs. Or, like a codex from the Middle Ages, erased and rewritten countless times, but an x-ray examination reveals how the different layers of different ages stack and build on top of each other. We live in an age when everything is possible.

Because the two are not mutually exclusive.

Yes; these things are to stay, as long as we are basically the same, physiologically speaking; i.e. until people need something to sit on, something to grab, until people are aware of the material impressions their environment. The core of these things might change; this object is a book, and at the same time it is a work of art, an equipment, a fetish object. It’s a matter of your point of view. It hasn’t been printed merely to make it possible to be read, to contain information.

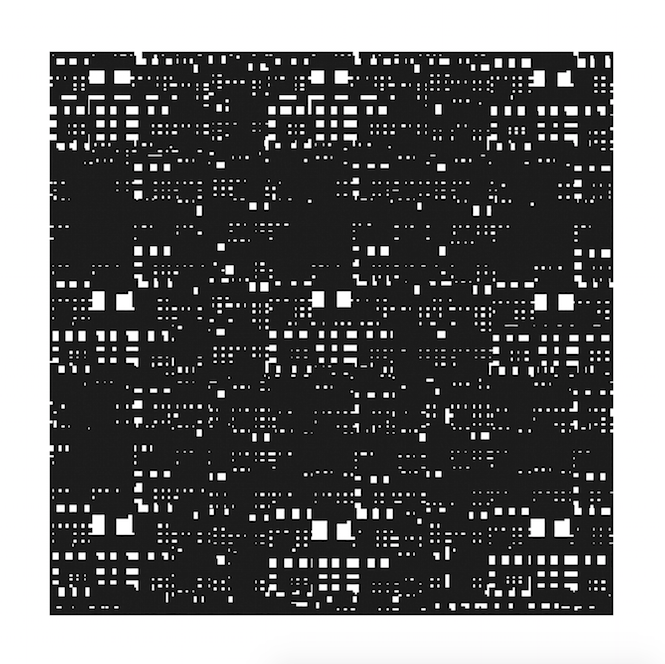

I just came up with something that spans through my whole oeuvre. Thanks to my mother, I come from a textile background, which has always been decisive. Since then, I realized that the knot, the smallest structural element of a carpet, is actually a pixel. Lately I’ve become fascinated by textile once again because of this; to identify the basic element of digital imaging with the knot, employed by traditional techniques. The carpet designer filled little squares on a design sheet for the future carpet. I’m intrigued by projecting old and new techniques on one another.

We grasp the world surrounding us as a large mosaic. I often compare the screens people stare at when working to the window of a church from the Middle Ages; glowing, projecting an image. How we make a book or a revealing, nice object out this beautiful vision, how we depict it, according to what system—that is what profession is. That is design.